High levels of stress in the banking system is impeding India's growth story. Looking at the credit offtake numbers, which fell from 13.5% in FY13 to less than 5% currently, it is clear that the health of the Indian macro economy is at stake here. The economy's lower than expected value add as well as slow job creation ability are other symptoms of this condition.Moreover, among emerging markets, the countryranks number two in terms of NPAs as a percent of total advances - a situation which embodies the overall business sentiment prevailing at this time.

On their part, banks have been able to arrest the growth of NPA to an extent, but not without costs. Asset portfolios of most banks have seen massive shifts towards investment grade accounts, leaving vulnerable corporates at risks. With opportunities to finance their operations dwindling, corporates are facing narrower options to continue their businesses sustainably. No quick solutions are visible as banks continue to battle the contagion of bad loans and its negative impact on their balance sheets. The RBI and the Ministry of Finance have come up with several initiatives to bring down the time required to resolve NPAs and free banking resources for productive uses - results are however yet to be seen.

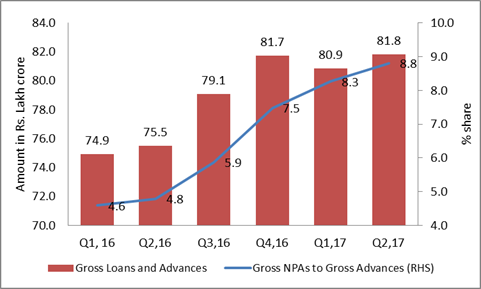

Source: CMIE; RBI

Banks are under pressure:

With over 16.6% in NPA and stressed assets, the country's banking system is among the most highly stressed in the world and will require more extensive interventions by the Ministry of Finance and the RBI. Towards this end, the Government's estimates that banks will have a capital requirement of nearly $28 billion in order to meet their Basel III obligation. In an environment where Indian banks are facing massive pressures for playing a bigger role in the country's development agenda while maintaining their business sustainability, it willhowever become all the more difficult to meet the requirements unaided. The Economic Survey 2015-16 has extensively debated the so called Twin Balance Sheet (TBS) problem that has in-turn resulted from the Non-Performing Asset (NPA) crises plaguing the banking system. The TBS explains the impact of non-performing loans on the balance sheets of not only commercial banks but also indebted corporates, which are no longer in a position to raise further debt from the market. This situation has slowed down the credit offtake to near negative levels and impeded fresh investments that drive GDP growth.

Source: RBI

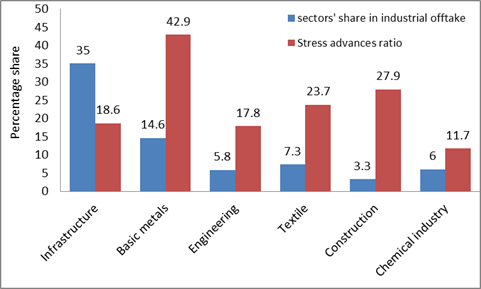

Declining Investments and demand for capital:

From the demand perspective, the Indian corporates on their part have been reeling under significant pressure. As an example, Infrastructure, which has the highest exposure to banking financial resources - records stress level exceeding 18%; similarly almost half of the Basic Metals exposure is classified as stressed. Construction sector, considered the most vulnerable at this time fares no better with a quarter of the entire exposure underperforming.

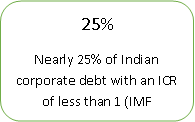

Results are apparent, with the Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), the very basic indicator of Capex constantly declining over the years and currently contributes to only 29.4% of GDP. Between 2000 and 2010, when the Indian economy was expanding at nearly 9% on average, GFCF averaged nearly 35%. As per World Bank data, the Domestic Credit to Private Sector in India has increased to 52% of GDP as against 25% in the 1980s. However, this high growth has resulted in unproductive capacity creation and risky investments that have now resulted in massive amounts of debt essentially becoming non-performing. With the fall in credit demand, it is evident that India Inc. doesn't wish to invest in capacity creation on account of excess capacities. At the same time the outlook for the demand is not very encouraging until current inventories clear and capacity utilization levels stabilise.

Underutilized capacities:

Currently, the average capacity utilization is less than 70% resulting in a weak GFCF. Further, Corporate Savings has been increasing and now stands at over 12% of GDP (averaging no more than 9%) which signals that the private sector is not planning an expansion.

The solution to the problem has been suggested in the form of a new Government backed Asset Management Company (AMC) called Public Sector Rehabilitation Agency (PARA) that will take over bad loans from Commercial Banks. The move will allow banks to focus on healthy loans and help heal their balance sheets.

The Current Plan: Insufficient recapitalization of banks & Institutional Backing

As per the Government of India's current recapitalization plan under the Indradhanush Scheme, $10.9 billion will be provided to banks in tranches until the year 2019. The remaining $17 billion equivalent will have to be raised by the banks;this could be mainly through Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds, equity (government disinvestment) or masala bonds. In the current circumstances however, such capital raising will not be an easy exercise. While Domestic Institutional Investors have taken a lead in Indian equity and bond space, it is clear that the entire quantum cannot be absorbed by them alone. Foreign Investors on their part have been the mainstay buyers of Indian debt but due to the current international volatility, it will be too farfetched to believe that they will entirely bail out Indian banks and help the latter meeting their capital requirements.

By way of internal accruals or other possible means, Indian banks are anyway under significant stress as rising provisioning has been impacting interest margins. In general, provisioning level is hovering at the 70% level (incorporating even healthy loans) and even large banks, which are considered stronger are recording a rise. According to the IMF's Global Financial Stability Report of 2017, in order to meet its provisioning requirements, a third of Indian banking system will require the equivalent of three years of net income. Even though banks have shown improvements in their profitability - mainly on account of better operating margins due to demonetization led record deposits, PAT as a percent of total income is just 2.4%, a far cry from the over 10% recorded in 2012. With these realities in the background, we therefore do not have confidence that banks will find enough resources sustainably to keep stress levels at bay.

What did the peers do?: China's war chest against NPA was equivalent to $500 billion; The USA's TARP Fund was worth $431 billion

When we talk about the $28 billion bailout, partially funded via public money, it is imperative to understand the sheer size of the Indian economy. Consistent growth of 7.5% over the next two decades will be unattainable for a country, who's banking sector remains stressed and hence is unable to finance a boom. While India retains the fastest growing global economy tag, its credit offtake growth of sub 5% will be insufficient to maintain the momentum. When we consider the case of China, considering the country has a 12-13 year head start over India, NPA levels in large banks touched almost 30% of assets in the early 2000s. Much like India's AQR, the Chinese identification of bad debt led to the formation of four Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs), jointly backed by the People's Bank of China (45%) and the Government (55%). The special purpose ARCsacquired bad loans from large Chinese banks and operationalized themselves through the issue of bonds (against the acquired assets). With banks balance sheets free of NPAs, offtake could restart and financing of China's capacity expansion continued unabated. Overall, the exercise cost the Chinese Government an estimated $500 billion between 1999 and 2005, when the economy was no bigger than India's current size. This kind of asset rehabilitation exercises have been successfully conducted by other Asian countries including Thailand, Japan and South Korea at the time of crises.

In India, since 70-75% of the bad loans are held by Public Sector Commercial Banks:

potentially $60-$100 billion may have to be managed by a public debt rehabilitation agency or bad bank, if India were to have such an agency. This arrangement may be built around the concept of other successful examples such as the $431 billion United States Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), United Kingdom's $60 billion UK Asset Resolution Company (UKAR) and Indonesia's $60 billion Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA). Such agencies function in a time bound fashion and are henceforth dissolved once the intentions are met. The arrangement can be more successful than the private Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) since issued Security Receipts (SRs) could be fully backed by the Government, reassuring investors.

Conclusion: India must not reinvent the wheel; must abstain from sending good money after the bad

Acuité strongly advocates that like its peers, India must create a special purpose vehicle to deal with the bad loans. Parallel to other innovative initiatives, a dedicated bad bank can be the most potent weapon against the current malaise. What we already know, from experience of other countries is that NPAscenario is a natural result of rapid growth and expansion of an economy. During the 1996 ASEAN crises, the Asian Tigers were massively impacted by unproductive loans and the result was a cleanup exercise that lasted years; it can be noted that nothing could be sustainably achieved here without a dedicated and specialized bad bank. The cases of China, Japan and Indonesia point towards the same direction and suggest the importance of separating the bad loans. This is the only way to reinvigorate banks. Even the US and UK could not escape the compulsion of creating such a scenario at the height of the subprime crises. It is therefore imperative for India to consider these examples and deliberateon its options wisely. Merely infusing capital and sending good money after the bad will exacerbate the situation and stress the already limited public finances - something that will not sustain the contagion successfully.

However, having said this, while a bad bank can be a onetime arrangement, it is imperative to ensure that any unsustainable future growth of bad loans is arrested. The regulators must ensure that banks appropriately streamline their operations, thereby aligning their lending strategies to suit their abilities. Also, appropriate frameworks must ensure that banks do not expose their balance sheets to exceptional risk. These measures will pave the way for fewer, consolidated, well capitalized banks with large concentrated exposures - in effect bulwarking a future spread of a system wide contagion.