Indian economy is at the crossroads but definitely not in a crisis. While the concerns on the growth tapering are valid and need to be addressed, predictions of a hard landing or a crash are highly premature and misplaced.

India has witnessed structural improvement in the macroeconomic milestones such as the fiscal deficit, consumer price inflation, foreign exchange reserves and FDI inflows over the last few years. These aspects have put the Indian economy on a robust platform and increased its ability to absorb potential shocks. However, slow private sector investments have been a matter of worry for some time and have started to be a visible constraining factor in the sustainability of growth and job creation in the economy.

Needless to say, the government has to take specific measures to put the growth curve back to the original alignment. Our suggestions include not just increased spending but targetted spending particularly in the infrastructure sector which can step up construction activities in the short to medium term and create jobs. A revival in the real estate and the MSME sectors through appropriate incentives for fresh investments should also be a focus area of the government given their potential to generate employment within a short time span.

With the publication of the latest quarterly growth figures for the Indian economy, market participants and economists have been working overnight, revising their growth estimates. The media is buzzing with stories of economic mismanagement and the growth crisis that we are confronted with. While the recent economic data is surely a matter of concern and needs to be responded to, hasty conclusions are never a panacea to our economic challenges.

The economy is not in the best of shape, But at the same time, it will be difficult to deny that the macroeconomic framework remains fairly robust, the growth weakness notwithstanding.

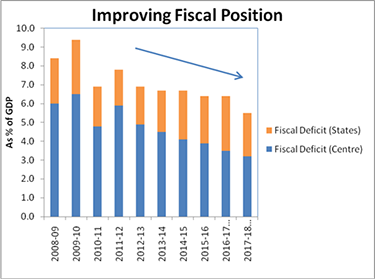

There is a structural improvement in the fiscal deficit at the consolidated level and particularly at the federal level since 2009-10. The fiscal deficit at the Centre, which was at 6.5% in 2009-10, has come down steadily and stood at an all-time low of 3.5% in 2016-17. While the deficits at the state level have been very sticky and difficult to reduce, the consolidated government deficit has dropped from 9.3% in 2009-10 to 6.4% in 2016-17. The consolidated debt to GDP has also witnessed an improvement from 70.6% of GDP in 2009-10 to 63.9% of GDP in 2016-17. This is a significant achievement in the Indian macroeconomic framework and reflects a positive orientation to fiscal discipline irrespective of the government at the Centre. Admittedly, it will be a challenge to stick to the fiscal consolidation path in the medium term, given the need for higher government spending in the infrastructure sector.

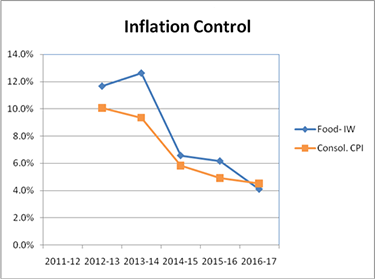

Inflation management has been one of the most significant achievements of RBI and also the government over the last three years. CPI annual average figures were in double digit in 2012-13 at 10.1% and have thereafter steadily climbed down to 4.5% in 2016-17 with RBI having set a target of 4.0%. While CPI figures have been further lower in the last one year and unlikely to sustain at those levels, the central bank's focus on inflation control has been highly successful.

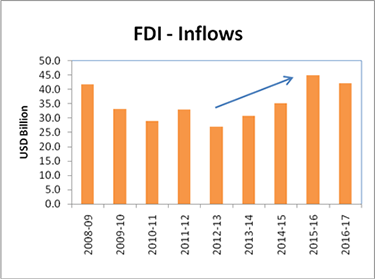

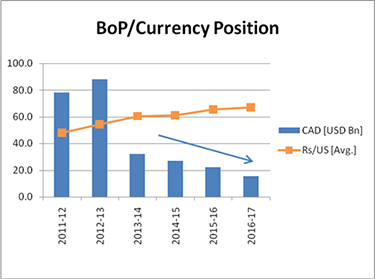

Our foreign exchange reserves are upwards of USD 400 billion as compared to the scenario in July 2013 when the rupee depreciated sharply. FDI flows to India have increased from USD 30.8 billion in 2013-14 to USD 44.9 billion in 2015-16 and USD 42.2 billion in 2016-17. This has helped to bridge a surge in the trade deficit and the current account deficit which has seen a spurt to USD 41.2 billion and USD 14.3 billion respectively in Q1 2017-18. This has also helped the rupee to be relatively stable vis-à-vis other currencies of emerging markets.

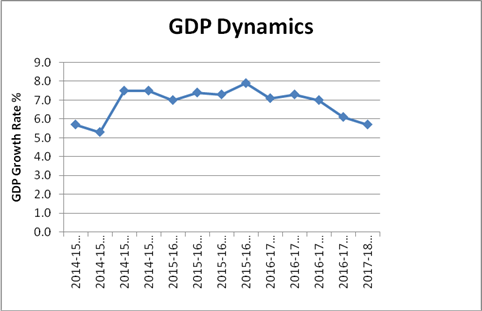

Now as regards growth in GDP, data does indicate a slowdown in the figures over the last 2-3 quarters. But it may be a bit early to cry ‘wolf' given the presence of events like demonetisation and GST implementation in fairly quick succession. While these events are expected to bring long-term benefits to the economic fabric through a broadening of the tax base, they have generated some uncertainty in the minds of consumers and producers, leading to a short- term impact on the growth figures.

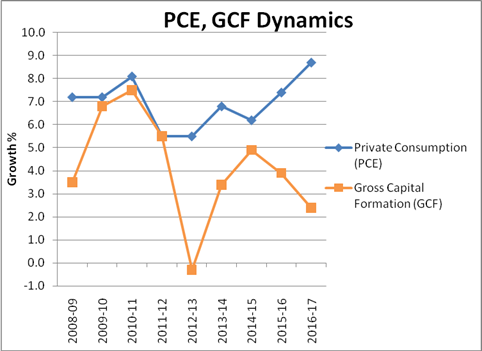

What can be the other underlying reasons for such a weakness in the growth trajectory? Private consumption has held on well over the last two years and its growth has been upwards of 7% though there may be some slip-up in the recent quarters.

However, there is clearly a distinct slowdown in the gross capital formation since 2011-12 and this has set the backdrop for growth softness. The growth in GCF dropped consistently from a high of 7.5% in 2010-11 to a low of 2.4% in 2016-17. Successive years of low growth rates in GCF have put constraints on the growth orbit and this is where the economy needs to do some solid work.

Most reports have talked about the continuous postponement in private sector capital expenditure as the primary factor for the low GCF growth. While moderate capacity utilisation in the large corporate sector has led to investment deferrals, the unprecedented slowdown in bank credit may not merely be a function of the latter.

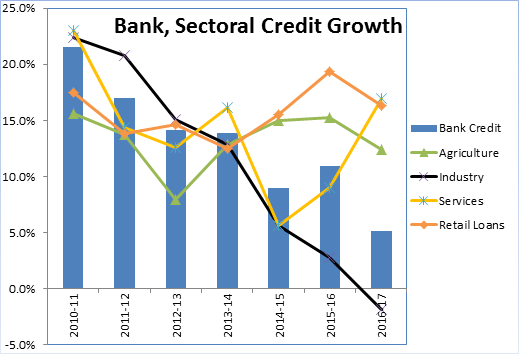

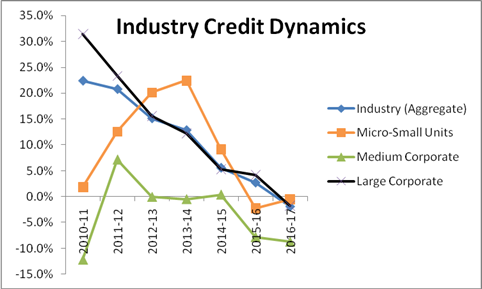

The bank credit growth has been on a declining trend since 2010-11 when it was at 21.5% and it has been in almost single digits over the last 3 years with the figure for 2016-17 at a multi-decadal low of 5.1%. The graphs above clearly reflect the challenge that we are experiencing on reviving credit growth in the economy.

Needless to say, the significant deterioration in the asset quality and capital position of the public sector banks (that still control 70% of the banking advances) has also been a key factor behind the credit growth dynamics. These banks have been averse to lending even to their existing and better quality clients. Six of these banks are currently under the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) of RBI, implying severe restrictions on their fresh disbursements. Many companies in the infrastructure sector (which are performing assets) are finding it difficult to get additional funding for their new projects and this is clearly delaying the progress in their construction activities.

The sector-wise credit growth trends also convey the fact that credit availability to the industry has suffered due to the structural challenges in the banking sector. RBI data shows that the credit growth to the industry segment has declined very sharply since 2013-14 and has actually been negative at -1.9% in 2016-17.

Further analysis of these data indicates that the situation is particularly worrisome in the MSME segments where the bank advances have been virtually stagnant at Rs. 4.7 lakh Cr over the last three years. Even if one accepts the argument on unfavourable credit environment, questions may still arise on the delivery efficiencies of the banking system to the MSME sector. More so, since retail NBFCs have been steadily building up a large loan portfolio in the MSME sector particularly through the loan against property (LAP) product. Wholesale NBFCs have been also quick in identifying the opportunity created in the corporate loan market and have been successful in scaling up their loan book over the last couple of years. However, NBFCs are not in a position to cater to the aggregate system requirements and banks need to step up and review their lending policy to MSMEs.

The road ahead

There are several measures and immediate measures that the government needs to take to pull up growth from the current slackness.

Factors that can facilitate growth of manpower intensive sectors:

As a nation, this is not the time to panic and be in a hurry to label the current scenario as a structural crisis. At the same time, the government can't afford to be complacent and believe that the current growth slippage is only a technical aberration. The need of the hour is to put in place immediate measures to facilitate growth while continuing to pursue long-term structural reforms.